I’m not sure how I missed author Cathy Carr’s debut middle-grade novel, 365 Days to Alaska, when it was published by Abrams in 2021 — but I am glad to have recently discovered it!

What I love most about the book, besides the satisfying storyline and relatable characters, is that it reverses a common trope found in books set in Alaska: newcomer arrives, undergoes culture shock, and learns to appreciate their new environment.

Carr’s novel reverses the settings. Rigel, her eleven-year-old main character, has grown up with a subsistence lifestyle in the Alaskan bush, off-road and off-grid. While Rigel loves her wilderness life, her older sister longs for civilization. Her younger sister, too, is eager to explore the outside world. When their parents’ marriage falls apart, their mother moves the girls to suburban Connecticut to live with their grandmother. Talk about culture shock!

Though the majority of the story is set in Connecticut, Alaska and the north are present throughout as Rigel and her sisters adjust from their old life to their new one. Carr does an admirable job of noting the details they navigate, everything from obvious amenities like running water, flush toilets, and electricity to subtleties, like the way people smile all the time, whether they mean it or not; eating food purchased from the grocery store, rather than harvested directly from the land; and figuring out how social hierarchies and school rules, stated and unstated, operate.

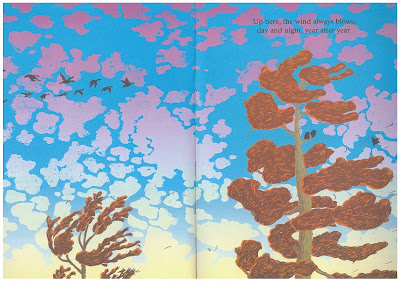

Cover of 365 Days to Alaska

by Cathy Carr

The title refers to Rigel’s secret agreement with her dad that if she can survive 365 days in Connecticut, he will find a way to bring her back to Alaska after one year. Rigel clings to his promise as she struggles to adjust, which drives much of the tension throughout the book.

For someone who has never lived in the Bush, or even been to Alaska, Carr does an unusually adept job of describing the lifestyle, environment, and mindsets of her Alaskan “bush rat” characters. In online interviews posted on her website, she attributes her accomplishment to several factors. First, her father lived and traveled in Alaska while in the Navy, so she grew up hearing stories and looking at photos about his experiences. This prompted a lifelong interest in reading everything she could find about the state. In her twenties, she had friends who lived, or wanted to live, off-the-grid, so she was exposed to information about what that lifestyle involves. Finally, she also found authenticity readers who lived in Alaska to vet her manuscript for accuracy.

You can learn more about the author, Cathy Carr, and her new middle-grade novel Lost Kites and Other Treasures, at cathycarrwrites.com.