The subtitle for this unique book reads “How a lonely orphan came to be accepted into a Tlingit clan.” Who is this orphan? A mouse!

First, a little background for non-Alaskan readers. The Tlingit Indians are indigenous people of Southeast Alaska. The Raven House of the book’s title is a clan house, used by the Indian community, in Haines, Alaska. You may have seen a photograph of the beautiful carving of a raven by renowned carver Nathan Jackson, which is attached to this building.

The story, a picture book, is told from the perspective of an orphaned mouse who stumbles into Raven House, attracted by the warmth emanating from a dryer vent as winter is setting in. Soon the little mouse observes the traditional dancing, drumming and singing practices that take place in the house, which is occupied by a man called “the caretaker.” Impressed by the dancers’ regalia, the mouse makes his own button-blanket, head band and drum from salvaged scraps. Soon he is practicing along with the Tlingit dance troupe, unobserved (he believes). Adventures and friendship ensue…

This interesting little story amuses and intrigues as much as it teaches. Tlingit cultural values are integral throughout, portrayed thoughtfully through the plot, characters, language, foreward, author’s note, glossary and art, rather than heavy-handed didacticism. Robert Davis, a Tlingit artist from the small village of Kake in Southeast Alaska, employs a traditional style of designs based on carving to represent all the characters, both people and animals.

Coupled with clean lines and plenty of white space, the overall effect is direct, unpretentious and engaging, the type of art that supports and enhances the story rather than overwhelming it with gorgeousness. This highly symbolic style of art, best known outside of Alaska in totem poles, is surprisingly effective, though it may require some interpretation for children unfamiliar with it. In terms of synthesizing the traditional and the modern, I especially enjoy the illustrations of the “dryer vent with glorious blast of steam,” the Christmas tree, and the caretaker, snoozing in his recliner amidst his regalia.Author Jan Steinbright dedicates Raven House Mouse to elder Austin Hammond (Daanawáak in Tlingit), who was the caretaker of Raven House for many years and “freely shared his wisdom and knowledge with all people.” He died in 1993. Steinbright explains in her author’s notes that inspiration for the story came from a little mouse that lived at Raven House with Mr. Hammond’s approval. This attitude of acceptance taught her a lesson about respect for all living things, which is reflected in this story.

Raven House Mouse includes a foreward, author’s notes, glossary, and three photos.

A blog about writing and reading children's books in the North.

Bookshelf

A mix of titles currently on my shelves.

Monday, May 9, 2011

Monday, May 2, 2011

Seven Things

Kate Boyan, the amazing beading artist and author/illustrator of The Blue Bead (see my earlier post here), passed on to me THE STYLISH BLOG AWARD. As far as I can tell, this high honor comes with the obligation to tell the world Seven Things People Don’t Know About Me.

In my case, it will have to be Seven Things MOST People Don’t Know About Me. I couldn’t think of seven things absolutely no one knows.

#1. I’m moving to Homer, Alaska at the end of the month. It’s true. After 29 years of living in lovely Willow, Alaska my husband and I are moving. Why? I’ve been offered the wonderful opportunity to be the new director of Homer’s fabulous public library.

#2. In one of my former (pre-Alaska) lives, I was a tree planter. I planted thousands of trees, all good, in mountains across the Pacific Northwest and Colorado. I still have the hoedad and caulk boots to prove it.

#3. I didn’t have a television for somewhere around 25 years. By choice. I got a lot of reading in. Try it sometime! You’ll be amazed.

#4. I grow three kinds of kale every summer: Toscano, Russian Red, and Winterbor.

#5. I wanted to be a writer and a tugboat captain when I was a kid. Instead, I became a writer and a librarian. Go figure. Maybe in my old age I’ll write my memoirs while volunteering on a boatmobile. (They do exist.)

#6. Not counting my high school newspaper, my first published piece was a sci-fi book review for a short-lived Cascadian journal called Seriatim.

#7. My favorite sections of the library are Fiction and 398.2. Always have been.

That’s it! And now....TA-DA…I pass on The Stylish Blog Award to my friend and fellow librarian/writer, Linda Shoup of the Purple Glasses Club. Congratulations! (No need to thank me. Have fun! Can’t wait to learn more about you.)

Monday, April 25, 2011

Public Lending Rights: Inquiring Minds Want to Know!

I asked Claire Eamer, author of Lizards in the Sky (most recently) and several other books, about her experience with PLR in Canada. Here are her comments. (Thank you, Claire!).

How did you find out about PLR?

Information about PLR is pretty widely distributed through writers’ organizations in Canada – including through informal listservs and meetings and workshops. Most writers will urge newly-published authors to registers, and organizations send out reminders.

How does it work, in your experience?

Once you’re registered the first time, the process is pretty painless. Each February, you get a cheque and a statement of how many of the 7 sample libraries your book was found in. In the same mailing is the registration form for any books published in the past year (or that you have neglected to register in the past). It’s a straightforward form where you provide title, ISBN numbers, number of pages…a few details like that. You attach photocopies of the title page, copyright page, and table of contents, and chuck it in the mail. And you’re done until next February. By the way, I’m right on top of this information because I filled out my registration for Lizards in the Sky two days ago and sent it off.

Do authors and illustrators split the per-book amount, as they typically do with royalties?

You indicate what level of responsibility you have for the book, which is based on the percentage of royalties you collect. For example, my first book was co-authored with a friend, so we each collect 50% of the PLR pay-out. For my other books, I collect 100%. However, I don’t have any picture books where I’m sharing royalties with an artist.

How does what you receive in PLR compare to what you receive in royalties for the same books?

I’ve made far more from PLR for my first book than I did in royalties, mainly because the book is long out of print and the publisher out of business but the book still consistently shows up in all 7 test libraries. No one has written a replacement book, so it’s still a reference that people use.

It’s difficult to compare the PLR payments to royalties because they depend on different things and work on different timeframes (see the example of my first book). I just checked my PLR statement and this year I got $339.22 for each of the recent books. That’s based on $48.46 per hit: i.e., a hit is the book showing up in one of the sample libraries. I got 7 out of 7 hits on each of the books, so I got the maximum pay-out. The older book gets a discounted rate of $29.08 per hit for books registered from 1986-1995.

Basically, you can’t live on PLR because it’s capped at about $5,000, but it’s certainly a nice addition to one’s income.

Do public lending rights make a difference in your ability to afford to work as a writer?

Yes. Every bit of income helps in this business. PLR will never be a major source of income, but it’s a part of the mosaic of income sources I put together.

In your opinion as a writer, are public lending rights a good idea? Why or why not?

Yes. PLR recognizes the value of the writers’ work, no matter how it is distributed. And, as I said above, every little bit of income helps.

In your opinion as a taxpayer, are public lending rights a good idea? Why or why not?

Yes. I regard public libraries as an extremely important public utility, and the books in them are an extremely important public resource. (I practically lived in the Saskatoon Public Library when I was a kid.) The books won’t be available if people don’t write them, so it’s important to recognize and reward – even at a modest level – the work that goes into creating them. However, I don’t want that reward to come through direct fees charges to library users. Free access to libraries is enormously important in building a literate society that is open to all of its members, not just those with sufficient financial resources. Therefore, the financial recognition to creators should be paid from the collective funds which we, as members of the society, contribute through taxes, according to our ability. I would add, as a Canadian, like healthcare!

How did you find out about PLR?

Information about PLR is pretty widely distributed through writers’ organizations in Canada – including through informal listservs and meetings and workshops. Most writers will urge newly-published authors to registers, and organizations send out reminders.

How does it work, in your experience?

Once you’re registered the first time, the process is pretty painless. Each February, you get a cheque and a statement of how many of the 7 sample libraries your book was found in. In the same mailing is the registration form for any books published in the past year (or that you have neglected to register in the past). It’s a straightforward form where you provide title, ISBN numbers, number of pages…a few details like that. You attach photocopies of the title page, copyright page, and table of contents, and chuck it in the mail. And you’re done until next February. By the way, I’m right on top of this information because I filled out my registration for Lizards in the Sky two days ago and sent it off.

Do authors and illustrators split the per-book amount, as they typically do with royalties?

You indicate what level of responsibility you have for the book, which is based on the percentage of royalties you collect. For example, my first book was co-authored with a friend, so we each collect 50% of the PLR pay-out. For my other books, I collect 100%. However, I don’t have any picture books where I’m sharing royalties with an artist.

How does what you receive in PLR compare to what you receive in royalties for the same books?

I’ve made far more from PLR for my first book than I did in royalties, mainly because the book is long out of print and the publisher out of business but the book still consistently shows up in all 7 test libraries. No one has written a replacement book, so it’s still a reference that people use.

It’s difficult to compare the PLR payments to royalties because they depend on different things and work on different timeframes (see the example of my first book). I just checked my PLR statement and this year I got $339.22 for each of the recent books. That’s based on $48.46 per hit: i.e., a hit is the book showing up in one of the sample libraries. I got 7 out of 7 hits on each of the books, so I got the maximum pay-out. The older book gets a discounted rate of $29.08 per hit for books registered from 1986-1995.

Basically, you can’t live on PLR because it’s capped at about $5,000, but it’s certainly a nice addition to one’s income.

Do public lending rights make a difference in your ability to afford to work as a writer?

Yes. Every bit of income helps in this business. PLR will never be a major source of income, but it’s a part of the mosaic of income sources I put together.

In your opinion as a writer, are public lending rights a good idea? Why or why not?

Yes. PLR recognizes the value of the writers’ work, no matter how it is distributed. And, as I said above, every little bit of income helps.

In your opinion as a taxpayer, are public lending rights a good idea? Why or why not?

Yes. I regard public libraries as an extremely important public utility, and the books in them are an extremely important public resource. (I practically lived in the Saskatoon Public Library when I was a kid.) The books won’t be available if people don’t write them, so it’s important to recognize and reward – even at a modest level – the work that goes into creating them. However, I don’t want that reward to come through direct fees charges to library users. Free access to libraries is enormously important in building a literate society that is open to all of its members, not just those with sufficient financial resources. Therefore, the financial recognition to creators should be paid from the collective funds which we, as members of the society, contribute through taxes, according to our ability. I would add, as a Canadian, like healthcare!

Monday, April 18, 2011

Public Lending Rights: How Do They Work?

Although the basic idea behind public lending rights (PLR) is the same across countries -- compensation to authors for use of their work in public libraries -- the details vary. According to Public Lending Rights International, three general approaches are used.

The first, found for example in Germany, Austria and the Netherlands, is based on copyright. In essence, libraries lease the right to provide authors’ works to the public, somewhat like they lease access to databases. In each country an organization representing writers deals with licensing and fee distribution. These transactions may be with the national or privincial government, or in some cases, directly with libraries. Under this arrangement, an author could choose to withhold use of their work in libraries as part of their copyright privilege.

A second type, used in the United Kingdom, considers PLR as an issue of compensation, rather than copyright. The UK’s 1979 PLR Act determined that government owes writers some remuneration for public use of their works in libraries. The act has nothing to do with licensing. A government agency oversees the program.

The third system is designed to support cultural goals. Scandinavian countries use PLR to encourage writing in their native languages. Authors receive no payment for books written in English, for example.

Denmark was the first country to initiate PLR in 1946. Norway followed in 1947, Sweden in 1954 and the UK in 1979. PLR are part of the European Union framework, as well. Another 13 countries have passed legislation regarding PLR but haven’t yet implemented systems for funding and payment.

PLR programs do not exist in the U.S., South America, Asia or Africa.

Various methods are used to calculate payments but the two most common are per library loan and per copy held by libraries. Statistics are gathered annually from a sampling of libraries to calculate payments. Criteria to qualify for PLR payments also vary by country; some apply only to books and authors, while others include illustrators, photographers, translators, and publishers. In some cases, audio books and music recordings are covered, as well.

Next: Canadian Claire Eamer on PLR in Canada.

The first, found for example in Germany, Austria and the Netherlands, is based on copyright. In essence, libraries lease the right to provide authors’ works to the public, somewhat like they lease access to databases. In each country an organization representing writers deals with licensing and fee distribution. These transactions may be with the national or privincial government, or in some cases, directly with libraries. Under this arrangement, an author could choose to withhold use of their work in libraries as part of their copyright privilege.

A second type, used in the United Kingdom, considers PLR as an issue of compensation, rather than copyright. The UK’s 1979 PLR Act determined that government owes writers some remuneration for public use of their works in libraries. The act has nothing to do with licensing. A government agency oversees the program.

The third system is designed to support cultural goals. Scandinavian countries use PLR to encourage writing in their native languages. Authors receive no payment for books written in English, for example.

Denmark was the first country to initiate PLR in 1946. Norway followed in 1947, Sweden in 1954 and the UK in 1979. PLR are part of the European Union framework, as well. Another 13 countries have passed legislation regarding PLR but haven’t yet implemented systems for funding and payment.

PLR programs do not exist in the U.S., South America, Asia or Africa.

Various methods are used to calculate payments but the two most common are per library loan and per copy held by libraries. Statistics are gathered annually from a sampling of libraries to calculate payments. Criteria to qualify for PLR payments also vary by country; some apply only to books and authors, while others include illustrators, photographers, translators, and publishers. In some cases, audio books and music recordings are covered, as well.

Next: Canadian Claire Eamer on PLR in Canada.

Monday, April 11, 2011

What Are Public Lending Rights and Why Should You Care?

Sometimes it’s downright amazing to find out how things are done in other countries. Take public lending rights (PLR) for example. In the United States the concept is virtually unknown, yet this system of reimbursing authors for use of their work exists in 28 countries, including Canada, Australia, Israel, New Zealand and most of Europe.

Writers in the U.S. or other non-PLR countries, just imagine this: Once or twice a year you receive a check in the mail for the use of your books in libraries.

It should take about three seconds to grasp the significance to you as a writer. With 16,671 public libraries, 99,180 school libraries and 3,827 academic libraries in the United States, even a very small amount per book (or per check-out, depending on the system used) could add up. With your royalty checks, your school visits, and your personal book sales, what kind of difference might that make?

As writers know all too well, most of them, even the well-published, do not make a living (or much of one) from their writing. Finding ways to afford to keep writing, or to carve out time and energy to write between family and jobs, is often as challenging as the actual work of writing.

As a writer, I love the idea that the creator of a book is compensated for its repeated use in public institutions, not just its one-time purchase. In a country like the U.S., where the self-employed pay dearly for such basics as healthcare, a system of PLR might make the difference between doing without medical care, going broke as a writer, taking a job at the expense of writing, or being able to keep up the good work.

But wait! When I put on my cardigan (libraries are so often drafty, it seems, and we must keep the heating bill down) and consider PLR as a librarian, my feelings are more muddled. My first thought is panic: Oh my gosh, now you want libraries to do what? Keep track of all that data AND pay people? With budget cuts already threatening and even closing libraries across the country? ARE YOU NUTS?

Sorry, I shouldn’t be shouting in the library.

Once I calm down and begin to think about it, I can see some reasons why libraries might support the idea. One is that libraries are all about facilitating the flow of information and ideas to their citizenry. If writers can’t afford to write, or if only the well-positioned can afford to write, we lose important perspectives as a society -- possibly even the very concepts, visions, and stories we need to solve our numerous problems.

Now throw digital books into the mix. We are in the midst of an on-going effort between publishers, libraries, writers, content developers, and consumers to figure out a working financial model for e-books in the marketplace, including libraries. Does the PLR concept have a role to play in that debate?

I’ll be looking at public lending rights over the next few posts and posting comments from several writers who receive them.

Writers in the U.S. or other non-PLR countries, just imagine this: Once or twice a year you receive a check in the mail for the use of your books in libraries.

It should take about three seconds to grasp the significance to you as a writer. With 16,671 public libraries, 99,180 school libraries and 3,827 academic libraries in the United States, even a very small amount per book (or per check-out, depending on the system used) could add up. With your royalty checks, your school visits, and your personal book sales, what kind of difference might that make?

As writers know all too well, most of them, even the well-published, do not make a living (or much of one) from their writing. Finding ways to afford to keep writing, or to carve out time and energy to write between family and jobs, is often as challenging as the actual work of writing.

As a writer, I love the idea that the creator of a book is compensated for its repeated use in public institutions, not just its one-time purchase. In a country like the U.S., where the self-employed pay dearly for such basics as healthcare, a system of PLR might make the difference between doing without medical care, going broke as a writer, taking a job at the expense of writing, or being able to keep up the good work.

But wait! When I put on my cardigan (libraries are so often drafty, it seems, and we must keep the heating bill down) and consider PLR as a librarian, my feelings are more muddled. My first thought is panic: Oh my gosh, now you want libraries to do what? Keep track of all that data AND pay people? With budget cuts already threatening and even closing libraries across the country? ARE YOU NUTS?

Sorry, I shouldn’t be shouting in the library.

Once I calm down and begin to think about it, I can see some reasons why libraries might support the idea. One is that libraries are all about facilitating the flow of information and ideas to their citizenry. If writers can’t afford to write, or if only the well-positioned can afford to write, we lose important perspectives as a society -- possibly even the very concepts, visions, and stories we need to solve our numerous problems.

Now throw digital books into the mix. We are in the midst of an on-going effort between publishers, libraries, writers, content developers, and consumers to figure out a working financial model for e-books in the marketplace, including libraries. Does the PLR concept have a role to play in that debate?

I’ll be looking at public lending rights over the next few posts and posting comments from several writers who receive them.

Monday, April 4, 2011

Fiddling Around with Poetry

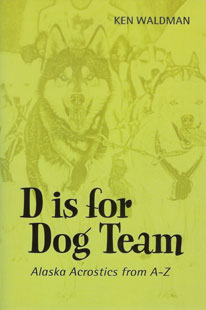

April is National Poetry Month so what better time to talk about Ken Waldman, a.k.a. Alaska’s fiddling poet. Ken is all about two things: making poems and playing his fiddle. Frequently, he puts the two together.

While most of Ken’s poetry books are for adults, he also has a book for kids: D is for Dog Team: Alaska Acrostics from A-Z. Turn the book over and upside down and you’ll find a second title, D is for Denali, between the same covers. The book contains two acrostic poems, each covering the alphabet from A-Z as it traverses Alaska. Some poems, like “P is for Palmer” and “E is for Eek Author’s Festival,” are about places, while others, like “G is for Glacier,” focus on specific aspects of living in Alaska. Ken has seen more of this vast state than most, having travelled just about everywhere for decades, performing, teaching, and writing. His poems reflect that intimacy.

D is for Dog Team comes with a CD that records Ken’s unique blend of music sprinkled with poems, including his two Alaska acrostics. Also for kids is Fiddling Poets on Parade: Alaskan Fiddling Poet Music for kids of all ages. (Follow the links for a sample listen.)

In honor of Poetry Month and Ken’s inspirational dedication to the calling, I offer my own small acrostic.

Ken is Ken,

energetic and eclectic, a rambling

North country guy.

Words flow and meander

as Alaska’s fiddling poet plays. He

lends his poems to

down-home, old-timey

music, the unpretentious kind.

Adds his own

nomadic observations.

I’m thinking that D is for Dog Team will inspire some Alaska acrostic writing among my students, too. Thanks, Ken!

P.S. Ken is the featured writer this month at 49 Writers. Check out his John Haines poems!

While most of Ken’s poetry books are for adults, he also has a book for kids: D is for Dog Team: Alaska Acrostics from A-Z. Turn the book over and upside down and you’ll find a second title, D is for Denali, between the same covers. The book contains two acrostic poems, each covering the alphabet from A-Z as it traverses Alaska. Some poems, like “P is for Palmer” and “E is for Eek Author’s Festival,” are about places, while others, like “G is for Glacier,” focus on specific aspects of living in Alaska. Ken has seen more of this vast state than most, having travelled just about everywhere for decades, performing, teaching, and writing. His poems reflect that intimacy.

D is for Dog Team comes with a CD that records Ken’s unique blend of music sprinkled with poems, including his two Alaska acrostics. Also for kids is Fiddling Poets on Parade: Alaskan Fiddling Poet Music for kids of all ages. (Follow the links for a sample listen.)

In honor of Poetry Month and Ken’s inspirational dedication to the calling, I offer my own small acrostic.

Ken is Ken,

energetic and eclectic, a rambling

North country guy.

Words flow and meander

as Alaska’s fiddling poet plays. He

lends his poems to

down-home, old-timey

music, the unpretentious kind.

Adds his own

nomadic observations.

I’m thinking that D is for Dog Team will inspire some Alaska acrostic writing among my students, too. Thanks, Ken!

P.S. Ken is the featured writer this month at 49 Writers. Check out his John Haines poems!

Monday, March 28, 2011

Siberian Tiger Tales

One of the things I love about traveling is discovering new books. While browsing the local bookstores in Juneau recently, I came across Spirit of the Siberian Tiger: Folktales of the Russian Far East, translated by Henry N. Michael and edited by Alexander B. Dolitsky, chairman of the Alaska-Siberia Research Center. The eye-catching cover, reproduced from a painting by Jason Morgan, is only a precursor of the delights to be found inside this beautiful piece of book making.

|

| Cover art by Jason Morgan. |

The four stories inside are translated from a longer Russian edition of literary folktales, which were written by Dmitriy Nagishkin and based upon stories from indigenous groups in the Russian Far East. This English collection focuses on stories in which the Siberian tiger plays a role and pays tribute to their importance, through art, poetry, storytelling and factual information. In a preface and several brief introductory chapters, Dolitsky explains that numbers of panthera tigris altaica are dwindling to the point of critical endangerment. Before launching into the folktales, he discusses the dominant role tigers have played in Native culture and introduces readers to the ethnic groups of the Siberian Far East. A foreword by Wallace Olson, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at the University of Alaska Southeast, summarizes the significance of folktales in general and these four specifically.

|

| From "The Little Girl Elga" in Spirit of the Siberian Tiger. Illustration by Gennadiy Pavlishin. |

The stories are intriguing on their own. Titles like “The Seven Fears,” “The Little Girl Elga,” “The Greedy Kanchuga” and “Kile Bamba and Loche-The Strongman” had me hooked even before I began reading. Told in a direct style that flows well, each ends with “Discussion Topics” that would prove useful for teachers. Interior illustrations by Russian artist Gennadiy Pavlishin are sumptuous, whether as chapter-concluding accents or full-page spreads. An index, glossary, bibliography, and transliteration table (Russian letters to English) make this a valuable educational resource, as well as an entertaining storybook with beautiful art.

Published by the Alaska-Siberia Research Center, 2008.

For adults, educators, and older children who have an interest in folk and fairy tales, or Russian and Siberian culture.

Monday, March 21, 2011

Library Story Time -- the Original Preschool Book Club!

I’m a huge fan of parents reading with their children – and that’s an understatement. As far as I’m concerned, it’s essential, right up there with food, clothing, and love. I’m also a fan of book clubs. I cherish the discoveries, conversations and the friendships I’ve made over books in the group I’ve belonged to for many years.

So I read with interest about “Mommy and Me” (or “Daddy and Me”) book clubs. Blogger, mom, and former kindergarten teacher Danielle Scribner writes about the preschool book club she organized and participates in at http://preschoolbookclub.blogspot.com/. It’s a great idea and I love seeing parents and children having so much fun with books and each other. It’s a win-win situation all around: children gain literacy and social skills, while parents enjoy time with their children and other adults.

It reminds me of my years leading pre-school story times as a public librarian. What a joy, introducing young children (and their parents) to stories and books! We had a wonderful time creating crafts and doing activities to extend the stories. Children browsed the bins and shelves of books and were excited to take home their new discoveries each week. Parents swapped child-rearing advice and encouraged each other through childhood stages and illnesses. Over time, friendships and bonds were formed that extended beyond the library.

If you think about it, public libraries all across the country, from big cities to tiny towns, are already providing preschool book clubs – week after week, year after year. Library Story Time is free and usually staffed by enthusiastic professionals or dedicated volunteers. Recently, for example, I received an e-mail from the Anchorage (Alaska) Municipal Library, announcing their upcoming activities. Lapsits, songs, crafts, special events – it’s all happening at the library.

So I say “hooray” for preschool book clubs, whether at home or at the library. Or even better, both.

So I read with interest about “Mommy and Me” (or “Daddy and Me”) book clubs. Blogger, mom, and former kindergarten teacher Danielle Scribner writes about the preschool book club she organized and participates in at http://preschoolbookclub.blogspot.com/. It’s a great idea and I love seeing parents and children having so much fun with books and each other. It’s a win-win situation all around: children gain literacy and social skills, while parents enjoy time with their children and other adults.

It reminds me of my years leading pre-school story times as a public librarian. What a joy, introducing young children (and their parents) to stories and books! We had a wonderful time creating crafts and doing activities to extend the stories. Children browsed the bins and shelves of books and were excited to take home their new discoveries each week. Parents swapped child-rearing advice and encouraged each other through childhood stages and illnesses. Over time, friendships and bonds were formed that extended beyond the library.

If you think about it, public libraries all across the country, from big cities to tiny towns, are already providing preschool book clubs – week after week, year after year. Library Story Time is free and usually staffed by enthusiastic professionals or dedicated volunteers. Recently, for example, I received an e-mail from the Anchorage (Alaska) Municipal Library, announcing their upcoming activities. Lapsits, songs, crafts, special events – it’s all happening at the library.

So I say “hooray” for preschool book clubs, whether at home or at the library. Or even better, both.

Tuesday, March 15, 2011

Sled Dogs and Their Humans

The third book I rediscovered this Iditarod season, Wind-Wild Dog by Barbara Joose, isn’t about the Iditarod at all. This tender tale portrays the relationship between a dog musher and a dog that must choose between following its wild nature and staying with the man. Evocative illustrations by Kate Kiesler extend the text to create a beautiful picture book story that explores human-canine relationships, as well as the capacity for wildness we share, in terms that even young children can understand. The soft oil paintings are spare, using body language and focus to express emotional drama. Joose includes a note at the end that provides information about Alaska

Saturday, March 12, 2011

Heroes, Human and Canine

The Iditarod is exciting and challenging, a world-class outdoor competition. No doubt about it. But what sets the Iditarod apart from other dog mushing races is its history. Every year, the race reminds us of the heroic 1925 endeavor that brought life-saving serum by dog team to an isolated Alaska community in the throes of a deadly diphtheria epidemic.

The Great Serum Race: Blazing the Iditarod Trail by Debbie Miller, illustrated by Jon Van Zyle (who has also run the race and creates the official Iditarod posters every year), is a factual and moving account of that historic struggle. The tragedy unfolding as diphtheria breaks out in Nome

Wednesday, March 9, 2011

Iditarod Tales

When the Iditarod sled dog race starts* in your hometown, it’s a big, barking deal.

Last Sunday hundreds (maybe thousands) of well-wishers lined the trail, waving to and encouraging the mushers, who were just beginning their 1,000-plus mile journeys to Nome. My friends and I skied to a nearby lake to join the festivities beneath a bright blue sky, with even more light reflecting off the expanse of snow all around us. Dozens of dogs trotted by, belonging to more than 60 teams. Their feet, swathed in colorful booties to protect their foot pads, bobbed up and down rhythmically like staccato notes against the white.

I’d been reading books about dog mushing and the Iditarod aloud to students all week and rediscovered several favorites in the process. First is Kiana's Iditarod, a down-home, on-the-trail picture book story about what it’s like to run this wild race. Written by Shelley Gill, an Alaskan who was only the fifth woman to complete the Iditarod, and illustrated by Shannon Cartwright, an artist who lives off-road in the Talkeetna Mountains, this oldie-goldie manages to convey information as well as excitement about the hazards and the competition along the trail. Although written in verse that is serviceable, but not always perfect, that flaw is forgivable in exchange for its authenticity, inviting illustrations, and dog’s-eye-view of the race. The colorful art is visually interesting and nearly capable of telling a story on its own. At 64 pages, Kiana's Iditarod is longer than the usual picture book for reading out loud, but the story moves quickly as lead dog Kiana races with her team. A map of the route, general note about the race, and glossary of dog mushing terms provide clear-cut, helpful information. For ages 4-8.

More to follow soon...

*The official start is in Anchorage. That is a ceremonial start. The "restart" -- when mushers and teams actually begin the journey by dog sled to Nome -- takes place in Willow.

Last Sunday hundreds (maybe thousands) of well-wishers lined the trail, waving to and encouraging the mushers, who were just beginning their 1,000-plus mile journeys to Nome. My friends and I skied to a nearby lake to join the festivities beneath a bright blue sky, with even more light reflecting off the expanse of snow all around us. Dozens of dogs trotted by, belonging to more than 60 teams. Their feet, swathed in colorful booties to protect their foot pads, bobbed up and down rhythmically like staccato notes against the white.

|

| Iditarod Sled Dog Race, 2011 |

More to follow soon...

*The official start is in Anchorage. That is a ceremonial start. The "restart" -- when mushers and teams actually begin the journey by dog sled to Nome -- takes place in Willow.

Tuesday, March 1, 2011

UAA / ADN Creative Writing Contest

The University of Alaska Anchorage and Anchorage Daily News are again sponsoring a creative writing contest, open to Alaska residents. The categories are nonfiction, fiction, and poems (up to three). Age groups are K-3, 4-6, 7-12 and adult. In addition to online and print publication, the winners will receive cash awards ranging from $25 to a $200 grand prize.

This excellent program is now in its 29th year. It's a great opportunity for would-be writers to take the plunge and for the public to discover new Alaskan writers. So Alaskans, don't be shy! Submit your best work by April 15, 2011 here.

This excellent program is now in its 29th year. It's a great opportunity for would-be writers to take the plunge and for the public to discover new Alaskan writers. So Alaskans, don't be shy! Submit your best work by April 15, 2011 here.

Monday, February 28, 2011

Flumbra and Alfie

Several months ago I wrote about some of the differences between Scandinavian and American picture books. One of my favorite examples of the openness in Nordic children’s books is a delightful picture book from Iceland, Flumbra: An Icelandic Folktale by Gudrún Helgadóttir. Ari, a little boy in Iceland, worries about giants, who are known to live in the mountains and occasionally steal misbehaving human children. When he asks Pappa for a story about giants, he hears about Flumbra. This giantess of old falls in love with a giant from another mountain. After a raucous romance, she returns home and later is blessed with eight baby giants, whom she loves and cares for like any human mother might. By the end of the tale, Ari is reassured and we, the readers, have a new appreciation for both mountains and giants.

This is the only American picture book I can think of with a breastfeeding mother depicted (even if she is a giant). Maybe the fact that it was published in 1986 has something to do with it. Was society more liberal then? Perhaps the publisher, Carolrhoda Books, was open to the story because at that time it was a relatively small press, located in Minneapolis, which is known for its Scandinavian roots.

Here’s another little example of Scandinavian frankness in a photo I took in Stockholm the last time I was there. It’s from a display of well-known Swedish children’s authors in a fabulous museum called Junibacken, which is devoted entirely to the world of children’s books, stories, theater, and music. The character is Alfie Atkins, from the books by Gunilla Bergström, some of which have been published in English (as well as other languages).

This is the only American picture book I can think of with a breastfeeding mother depicted (even if she is a giant). Maybe the fact that it was published in 1986 has something to do with it. Was society more liberal then? Perhaps the publisher, Carolrhoda Books, was open to the story because at that time it was a relatively small press, located in Minneapolis, which is known for its Scandinavian roots.

Here’s another little example of Scandinavian frankness in a photo I took in Stockholm the last time I was there. It’s from a display of well-known Swedish children’s authors in a fabulous museum called Junibacken, which is devoted entirely to the world of children’s books, stories, theater, and music. The character is Alfie Atkins, from the books by Gunilla Bergström, some of which have been published in English (as well as other languages).

It’s meant to be humorous and not at all in bad taste. A joke – something like “B as in behind” or "B is for bottom" in English. Still, it’s not something you’re likely to see celebrated in a children’s museum display in the U.S!

Wednesday, February 23, 2011

Trust

Last week I was fortunate to hear two talented speakers who make beautiful picture books discuss their work. At the Alaska Library Conference in Juneau, editor Allyn Johnston of Beach Lane Books spoke about picture books she admires and why she likes them. Author/illustrator Marla Frazee explained the artistic process that goes into her work, which includes All the World and A Couple of Boys Have the Best Week Ever, both Caldecott Honor books. The two women often work together and it was clear that they have the kind of synergistic professional relationship that most writers and illustrators long for.

What books did Ms. Johnston mention as stellar examples? To mention a few: Hattie and the Fox by Mem Fox, for the brilliance of the page turns and the clever use of pattern and repetition. Caldecott Medal winner Kitten’s First Full Moon by Kevin Henkes, for its spare, direct text so well integrated with the art. The Carrot Seed, a classic from 1945 by Ruth Krauss, again for its sparse text and simple but evocative illustrations. And of course, Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, winner of the 1964 Caldecott.

Both Ms. Johnston and Ms. Frazee talked about open-endedness, leaving room in the text for the artist to engage and contribute to the story. Notice that all the books mentioned use spare but effective sentences and much of the art makes ample use of white space.

Their talks were a reminder to me as a writer to sometimes just shut up. Writers are by nature word people, at least on paper. If, like me, you are not an illustrator it can be hard to hand your story over to people you don’t know. I find in myself a tendency to want to make sure “they” are going to “get it,” to understand my story and share my vision for it.

But the best picture books are not about competently illustrated stories. They are a fusion of words and art that complement each other to make something better than either could be on its own. Something like a happy marriage, one could say. And like a happy marriage, that takes some serious trust.

My take-away from these talks is to increase my trust level and try harder to find the right words, even if that means fewer of them.

What books did Ms. Johnston mention as stellar examples? To mention a few: Hattie and the Fox by Mem Fox, for the brilliance of the page turns and the clever use of pattern and repetition. Caldecott Medal winner Kitten’s First Full Moon by Kevin Henkes, for its spare, direct text so well integrated with the art. The Carrot Seed, a classic from 1945 by Ruth Krauss, again for its sparse text and simple but evocative illustrations. And of course, Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, winner of the 1964 Caldecott.

Both Ms. Johnston and Ms. Frazee talked about open-endedness, leaving room in the text for the artist to engage and contribute to the story. Notice that all the books mentioned use spare but effective sentences and much of the art makes ample use of white space.

Their talks were a reminder to me as a writer to sometimes just shut up. Writers are by nature word people, at least on paper. If, like me, you are not an illustrator it can be hard to hand your story over to people you don’t know. I find in myself a tendency to want to make sure “they” are going to “get it,” to understand my story and share my vision for it.

But the best picture books are not about competently illustrated stories. They are a fusion of words and art that complement each other to make something better than either could be on its own. Something like a happy marriage, one could say. And like a happy marriage, that takes some serious trust.

My take-away from these talks is to increase my trust level and try harder to find the right words, even if that means fewer of them.

Wednesday, February 16, 2011

Lizards in the Sky -- Yikes!

Most kids like books about animals, especially critters that are cute or unusual. For a certain subset of young readers – primarily, but not always, boys – interest in odd animals borders on obsession.

These young enthusiasts know far more about animals than I ever will. Lizards in the Sky: Animals Where You Least Expect Them by Canadian Claire Eamer is perfect for such kids, as well as general-interest readers. Though it has plenty of eye-catching and informative pictures, this is at heart a science book, not fluff. The theme of the book is animals that live in unexpected places and the adaptations they make to survive. With hooks like “A snake, flat as a ribbon, gliding overhead?” and “Bomb-throwing worms” to lure readers into the main text, the book knows its audience. Organized into chapters based on general environment – water, land, desert, air, darkness, and cold – it covers a range of creatures, from microscopic to large, looking at the kinds of adaptations they use to live in various habitats.

One aspect of the book I don’t care for is the use of spot illustrations by Sir John Tenniel, from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. The intent was probably to enliven the format with a bit of fun and fancy. But to me, the juxtaposition of fanciful with scientific is incongruous. Nonetheless, this is a small quibble and quite possibly a personal preference.

Author Claire Eamer is a science writer who lives in the Yukon. Her previous books include Spiked Scorpions & Walking Whales; Super Crocs & Monster Wings and Traitor’s Gate and Other Doorways to the Past.

I’ll put this book in my school library, knowing full well it will prompt a conversation something like this:

These young enthusiasts know far more about animals than I ever will. Lizards in the Sky: Animals Where You Least Expect Them by Canadian Claire Eamer is perfect for such kids, as well as general-interest readers. Though it has plenty of eye-catching and informative pictures, this is at heart a science book, not fluff. The theme of the book is animals that live in unexpected places and the adaptations they make to survive. With hooks like “A snake, flat as a ribbon, gliding overhead?” and “Bomb-throwing worms” to lure readers into the main text, the book knows its audience. Organized into chapters based on general environment – water, land, desert, air, darkness, and cold – it covers a range of creatures, from microscopic to large, looking at the kinds of adaptations they use to live in various habitats.

One thing I really like about the book is that although the tone is conversational, it doesn’t talk down to kids. An appendix gives the scientific names for each animal discussed, chapter by chapter. A list of books for “Further Reading” is included, as well as a “Selected Bibliography” and a thorough index, details that are much appreciated by librarians and budding scientists.One aspect of the book I don’t care for is the use of spot illustrations by Sir John Tenniel, from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. The intent was probably to enliven the format with a bit of fun and fancy. But to me, the juxtaposition of fanciful with scientific is incongruous. Nonetheless, this is a small quibble and quite possibly a personal preference.

Author Claire Eamer is a science writer who lives in the Yukon. Her previous books include Spiked Scorpions & Walking Whales; Super Crocs & Monster Wings and Traitor’s Gate and Other Doorways to the Past.

I’ll put this book in my school library, knowing full well it will prompt a conversation something like this:

Future biologist earnestly informs me, “Mrs. Dixon, did you know that naked mole rat queens give birth to more than a thousand babies?”

I gasp.

“Not all at once,” he goes on to explain, delighted.

I gasp.

“Not all at once,” he goes on to explain, delighted.

“Thank goodness!” I reply.

And thank goodness for writers like Claire Eamer, who make exploring the natural world so interesting.

And thank goodness for writers like Claire Eamer, who make exploring the natural world so interesting.

Sunday, February 6, 2011

Interview with Debby Dahl Edwardson

A while ago I wrote about Blessing's Bead, a wonderful novel by Barrow resident Debby Dahl Edwardson. Debbie has been kind enough to answer some questions about her writing life. Her next book, My Name is Not Easy, is going to press soon with Marshall Cavendish.

Debby, I know you’ve lived in Barrow for over 30 years. I’m curious about what brought you there in the first place. It is rather out of the way for casual visiting! Would you mind talking about how and why you first came to Alaska; where else in Alaska you spent time; and how/why you got to Barrow?

I came to Alaska for adventure. I had just graduated from college in Colorado. A group of us were living in New Mexico and decided to drive north to Alaska to work on the Pipeline. For me it became a journey of discovery that has yet to end. I ended up in Barrow because my husband is Inupiaq and Barrow is his home. I moved to Barrow sight unseen, in fact, knowing that it would become my permanent home. It was February of 1980—a time of intense cold and blindingly bright sun. A strong, resilient and ultimately joyful people were bringing in sled loads of caribou and piling huge blocks of crystalline ice outside there homes for drinking water. I was enchanted.

You and I share a common denominator in that as young adults we both spent time in Scandinavia before coming to Alaska – you in Norway, I in Sweden. My time in Sweden was a strong influence in turning my interest northward to Alaska. Was that the case for you, too?

I guess that growing up in Minnesota, living in Norway and settling in Alaska have all fed into my identity as a northerner. My family instilled in me a fierce pride in my Norwegian heritage. My husband, who is Inupiaq, is also part Norwegian so for us there is always a sense of strong Norwegian-Alaskan ties.

Do you maintain connections with people in Norway? Snakker du norsk? (I think I just asked if you speak Norwegian.)

Ya, Jeg snakker norsk, men det har vært lenge siden… no, sadly I have pretty much lost connection with most of the people I knew in Norway. And although I have always wanted to go back, seven children and a busy life have sent me in other directions. My oldest daughter, who is a filmmaker, was invited to present her work at a Sámi film festival in Northern Norway several years ago. This daughter was also an exchange student in Sweden and my youngest daughter was an exchange student in Denmark—so in a way we have extended our Scandinavian connections. And I did actually receive a surprise email form a Norwegian classmate, recently.

He said he was waiting for a bus, listening to his ipod, and when the song “Bye, Bye Miss America Pie” came on and he remembered, suddenly, the first time he’d heard the song. It was played for him by an American Girl by the name of Debby Dahl. He had seen my website and remembered me.

The ways in which the internet connects us are truly amazing.

Living anywhere in Alaska – even Anchorage – is different from living in the Lower 48 states. For most people it requires some adjustment and the learning of new skills. It seems to me that living above the Arctic Circle and marrying into the Inupiaq culture would require significant adjustment and learning, including a non-Western language. Was that difficult for you? How long did it take for you to feel that this was home?

I was thinking of this when I was at Disneyworld recently, attending the NCTE/ALAN conference. It seemed like such an alien place to me! The truth is, that at this point in my life I often face culture shock when I travel south.

I think that living in Norway and learning another culture and language prepared me for the Inupiaq cultural immersion experience that has shaped me into the person I am today. And truly, there was a lot about the Inupiaq worldview that just made sense to me. It helped, also, that I had a good teacher, a cultural mentor who taught me to see the world through his eyes. I married this man.

The odd thing about Alaska was that I never intended to make it my permanent home. I’ve always had wanderlust and I used to think I would just keep traveling and experiencing all the wonderful places the world has to offer. Even after I had married into the culture and lived here a long time, part of me was still keenly aware of the fact that I was living far from my home. I don’t know exactly when it happened, but one day I realized that I was home, in every sense of the word. I actually consider myself to be bicultural at this point. The benefit of this is that I don’t really have to do a lot of research for the books I write—my life itself is the research!

About the book: Where did you get the idea for the bead as a motif to span the generations and unite the two main characters in the novel? Is there a real-life bead that inspired you?

There is a real life bead. In fact the bead on the cover of the book is the real bead that inspired the use of the fictional bead in the story. It was given to my husband and had belonged to an old woman in Point Hope. He was told him it would protect him. I’ve known and been fascinated by trade beads for many years, especially the Russian blues, which were indeed considered very valuable.

Authors usually have little or no control over the covers for their books. Is there a story behind the cover of Blessing’s Bead? I find the photograph of the girl to be evocative, almost haunting. Or was it arranged by editors and art directors? How do you feel about the cover?

Ah, now here’s a story! In fact the girl on the cover of the book is my middle daughter, Susan, whose Inupiaq name is Aaluk (as is one of the book’s main characters.) How did this happen? Well, although it is indeed unusual, my editor, Melanie Kroupa, then at Farrar Straus and Giroux, involved me every step of the way on the cover design. When it became clear that they wanted to do a photo cover—I started sending photos of local Barrow girls (my nieces) who I thought looked the part. None of them had quite the right expression, however. Out of desperation, I staged a photo shoot with my daughter who is an actress and could, I knew, get in character. However, neither she nor I thought she looked “Inupiaq enough.” The full story of the cover—and my thoughts about it, which are actually kind of complex, can be found here.

Debby, I know you’ve lived in Barrow for over 30 years. I’m curious about what brought you there in the first place. It is rather out of the way for casual visiting! Would you mind talking about how and why you first came to Alaska; where else in Alaska you spent time; and how/why you got to Barrow?

I came to Alaska for adventure. I had just graduated from college in Colorado. A group of us were living in New Mexico and decided to drive north to Alaska to work on the Pipeline. For me it became a journey of discovery that has yet to end. I ended up in Barrow because my husband is Inupiaq and Barrow is his home. I moved to Barrow sight unseen, in fact, knowing that it would become my permanent home. It was February of 1980—a time of intense cold and blindingly bright sun. A strong, resilient and ultimately joyful people were bringing in sled loads of caribou and piling huge blocks of crystalline ice outside there homes for drinking water. I was enchanted.

You and I share a common denominator in that as young adults we both spent time in Scandinavia before coming to Alaska – you in Norway, I in Sweden. My time in Sweden was a strong influence in turning my interest northward to Alaska. Was that the case for you, too?

I guess that growing up in Minnesota, living in Norway and settling in Alaska have all fed into my identity as a northerner. My family instilled in me a fierce pride in my Norwegian heritage. My husband, who is Inupiaq, is also part Norwegian so for us there is always a sense of strong Norwegian-Alaskan ties.

Do you maintain connections with people in Norway? Snakker du norsk? (I think I just asked if you speak Norwegian.)

Ya, Jeg snakker norsk, men det har vært lenge siden… no, sadly I have pretty much lost connection with most of the people I knew in Norway. And although I have always wanted to go back, seven children and a busy life have sent me in other directions. My oldest daughter, who is a filmmaker, was invited to present her work at a Sámi film festival in Northern Norway several years ago. This daughter was also an exchange student in Sweden and my youngest daughter was an exchange student in Denmark—so in a way we have extended our Scandinavian connections. And I did actually receive a surprise email form a Norwegian classmate, recently.

He said he was waiting for a bus, listening to his ipod, and when the song “Bye, Bye Miss America Pie” came on and he remembered, suddenly, the first time he’d heard the song. It was played for him by an American Girl by the name of Debby Dahl. He had seen my website and remembered me.

The ways in which the internet connects us are truly amazing.

Living anywhere in Alaska – even Anchorage – is different from living in the Lower 48 states. For most people it requires some adjustment and the learning of new skills. It seems to me that living above the Arctic Circle and marrying into the Inupiaq culture would require significant adjustment and learning, including a non-Western language. Was that difficult for you? How long did it take for you to feel that this was home?

I was thinking of this when I was at Disneyworld recently, attending the NCTE/ALAN conference. It seemed like such an alien place to me! The truth is, that at this point in my life I often face culture shock when I travel south.

I think that living in Norway and learning another culture and language prepared me for the Inupiaq cultural immersion experience that has shaped me into the person I am today. And truly, there was a lot about the Inupiaq worldview that just made sense to me. It helped, also, that I had a good teacher, a cultural mentor who taught me to see the world through his eyes. I married this man.

The odd thing about Alaska was that I never intended to make it my permanent home. I’ve always had wanderlust and I used to think I would just keep traveling and experiencing all the wonderful places the world has to offer. Even after I had married into the culture and lived here a long time, part of me was still keenly aware of the fact that I was living far from my home. I don’t know exactly when it happened, but one day I realized that I was home, in every sense of the word. I actually consider myself to be bicultural at this point. The benefit of this is that I don’t really have to do a lot of research for the books I write—my life itself is the research!

About the book: Where did you get the idea for the bead as a motif to span the generations and unite the two main characters in the novel? Is there a real-life bead that inspired you?

There is a real life bead. In fact the bead on the cover of the book is the real bead that inspired the use of the fictional bead in the story. It was given to my husband and had belonged to an old woman in Point Hope. He was told him it would protect him. I’ve known and been fascinated by trade beads for many years, especially the Russian blues, which were indeed considered very valuable.

Authors usually have little or no control over the covers for their books. Is there a story behind the cover of Blessing’s Bead? I find the photograph of the girl to be evocative, almost haunting. Or was it arranged by editors and art directors? How do you feel about the cover?

Ah, now here’s a story! In fact the girl on the cover of the book is my middle daughter, Susan, whose Inupiaq name is Aaluk (as is one of the book’s main characters.) How did this happen? Well, although it is indeed unusual, my editor, Melanie Kroupa, then at Farrar Straus and Giroux, involved me every step of the way on the cover design. When it became clear that they wanted to do a photo cover—I started sending photos of local Barrow girls (my nieces) who I thought looked the part. None of them had quite the right expression, however. Out of desperation, I staged a photo shoot with my daughter who is an actress and could, I knew, get in character. However, neither she nor I thought she looked “Inupiaq enough.” The full story of the cover—and my thoughts about it, which are actually kind of complex, can be found here.

Monday, January 31, 2011

Back to Basics

After venturing into the world of digital books, it’s time (for me, anyway) to veer back to basics: my all-time favorite cardboard book. In keeping with the focus of this blog, that beloved book happens to have been written by a Dane who worked for Bonniers, the eminent Swedish publisher, before moving to the U.S.

Spoiler warning for friends and relatives: I nearly always give this book as a baby present. Every time I go to purchase one, I’m afraid it will be out of print, so I buy several. Amazingly, this little gem has been in print since 1963, when it was first published by Golden Books.

And the title is...non-electronic drum roll, please...I am a Bunny, written by Ole Risom and illustrated by Richard Scarry.

Why do I love it so? Because both the text and art are a perfect combination of simplicity, detail, and imagination. The story is simple, a series of one-sentence descriptions of Nicholas the bunny’s activities through the seasons. But who can resist a narrative that begins like this:

The words are direct and to the point, yet when read aloud they sound lyrical. While the words resonate, we are looking at Nicholas, who is looking straight at us, with his adorable Richard Scarry bunny face, long pink ears, and red overalls. Next we notice a mother robin in his tree, feeding her three hungry chicks a worm.

Cardboard books don’t always get the attention they deserve. Because they are inexpensive, less effort is sometimes put into their production. These days, many are simply resized versions of successful picture books for older children. But cardboard books are a young child’s first, nearly indestructible, introduction to written stories. They should be age-appropriate and include the best work writers, illustrators, and publishers can muster – even in the mass-market trade.

Ole Risom understood that during his long career making books for children, from 1952 to 1972 at Golden Books Western Press and 1972 to 1990 at Random House. During that time he worked with Stan and Jan Berenstain (known for their Berenstain Bears series), Marc Brown (famous for his Arthur books and TV series), Laurent de Brunhoff (the Babar books), Jim Henson (of Sesame Street fame), Leo Lionni (author/illustrator of Inch by Inch, Swimmy, A Color Of His Own and many others), Charles M. Schulz (creator of Charlie Brown) and Dr. Seuss, as well as Richard Scarry.

Risom died at the age of 80 in 2000. He had a daughter, Camilla; a son, Christopher; and another son named...Nicholas.

Spoiler warning for friends and relatives: I nearly always give this book as a baby present. Every time I go to purchase one, I’m afraid it will be out of print, so I buy several. Amazingly, this little gem has been in print since 1963, when it was first published by Golden Books.

And the title is...non-electronic drum roll, please...I am a Bunny, written by Ole Risom and illustrated by Richard Scarry.

Why do I love it so? Because both the text and art are a perfect combination of simplicity, detail, and imagination. The story is simple, a series of one-sentence descriptions of Nicholas the bunny’s activities through the seasons. But who can resist a narrative that begins like this:

I am a bunny.

My name is Nicholas.

I live in a hollow tree.

The words are direct and to the point, yet when read aloud they sound lyrical. While the words resonate, we are looking at Nicholas, who is looking straight at us, with his adorable Richard Scarry bunny face, long pink ears, and red overalls. Next we notice a mother robin in his tree, feeding her three hungry chicks a worm.

Cardboard books don’t always get the attention they deserve. Because they are inexpensive, less effort is sometimes put into their production. These days, many are simply resized versions of successful picture books for older children. But cardboard books are a young child’s first, nearly indestructible, introduction to written stories. They should be age-appropriate and include the best work writers, illustrators, and publishers can muster – even in the mass-market trade.

Ole Risom understood that during his long career making books for children, from 1952 to 1972 at Golden Books Western Press and 1972 to 1990 at Random House. During that time he worked with Stan and Jan Berenstain (known for their Berenstain Bears series), Marc Brown (famous for his Arthur books and TV series), Laurent de Brunhoff (the Babar books), Jim Henson (of Sesame Street fame), Leo Lionni (author/illustrator of Inch by Inch, Swimmy, A Color Of His Own and many others), Charles M. Schulz (creator of Charlie Brown) and Dr. Seuss, as well as Richard Scarry.

Risom died at the age of 80 in 2000. He had a daughter, Camilla; a son, Christopher; and another son named...Nicholas.

Friday, January 28, 2011

Guess What? Kids Are Still Reading Books

Digital apps and e-books may be getting most of the buzz these days but a recent survey shows some reassuring results for those of us who love children’s books (the paper kind).

According to the findings of this survey, commissioned by Bowker/PubTrack and the Association of Booksellers for Children, books are still the top media for children ages 0-6, even in households that can afford the toys of technology. More good news: even tech-busy teens like reading books for fun, rating it third on their lists. So far, they’re reading print books; less than 20% read e-books.

Good news for libraries, too: young children get most of their books from public and school libraries. Librarians already knew that – but it’s good to have some data to confirm it.

Another non-surprise is that women purchase 70% of books for children.

At the same time, Amazon just announced that sales of digital books through their site have exceeded sales of paperback books. Last July purchases of e-books surpassed hardcovers.

No doubt about it -- we live in interesting times.

Sources

Publishers Weekly. Winter Institute: Children’s Books in a Digital Age.

Amazon.com. Amazon.com Announces Fourth Quarter Sales up 36% to $12.95 Billion

According to the findings of this survey, commissioned by Bowker/PubTrack and the Association of Booksellers for Children, books are still the top media for children ages 0-6, even in households that can afford the toys of technology. More good news: even tech-busy teens like reading books for fun, rating it third on their lists. So far, they’re reading print books; less than 20% read e-books.

Good news for libraries, too: young children get most of their books from public and school libraries. Librarians already knew that – but it’s good to have some data to confirm it.

Another non-surprise is that women purchase 70% of books for children.

At the same time, Amazon just announced that sales of digital books through their site have exceeded sales of paperback books. Last July purchases of e-books surpassed hardcovers.

No doubt about it -- we live in interesting times.

Sources

Publishers Weekly. Winter Institute: Children’s Books in a Digital Age.

Amazon.com. Amazon.com Announces Fourth Quarter Sales up 36% to $12.95 Billion

Saturday, January 22, 2011

iPad Stories Worth Reading (and Playing With)

Kirkus Reviews, a respected book reviewer from the library world, has started reviewing iPad storytelling apps. Librarian that I am, I began my own inquiry into the world of iPad stories with five titles recommended on their “Best of Children's Book iPad Apps 2010.” (Who wants to download and sort through a bunch of clinkers to get to the good stuff?) If you're looking for good apps, you might want to start with these or others on the Kirkus list.

PopOut! The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter and developed by Loud Crow Interactive, Inc., combines the traditional look of Potter’s work with the feel of a pop-out/lift-the-tab book – except the manipulation is digital. Layers give a 3-D effect, with wriggling, spring-loaded bunnies, free-floating leaves and berries, and digital tabs that slide the characters around to create movement. Classical music and twittering birds help set the scene for the tale, which can be read silently or narrated. Words are highlighted as they are read aloud, making it easier to follow along. It’s great fun to slide Peter under the fence with a moveable tab, with the added plus that this tab will never bend and break. A bookmark tab on every page pulls down a thumbnail storyboard for selecting pages, a handy navigation feature. My only quibble with the app is this: with narration on, the sounds that busy fingers can initiate by touching characters compete with the telling. I would prefer them to pause until the text is read, or chatter more quietly. In all other aspects, it’s a lovely production that honors and extends the original. For ages 2+. (Also available for iPhone.)

Teddy’s Day is based on a 1994 story by Bruno Hächler and illustrator Birte Müller. App developer Auryn, Inc. has transformed a sweet, imaginative story into a sweet, imaginative story chockfull of creative surprises and interactive opportunities. Narration by a young girl sets the child’s-view tone of the tale. I love the pacing of the story and interactions. If you try to move through too quickly, you’ll miss the fun. Instead, after the text is spoken, on-screen highlights briefly shimmer, indicating opportunities for further exploration. These interactions lead you deeper into the story world. Another great feature is the chance to digitally paint pictures, which are then incorporated into the illustration. A spot-on story, interactions that enhance the telling, interesting perspectives, and opportunities to be part of the creative process combine wonderfully to tickle the imagination. For ages 3-7.

Alice – yes, the Alice of Wonderland fame by Lewis Carroll – combines the classic illustrations by Sir John Tenniel with pop-up style in this app from Atomic Antelope. Lush colors are set against a background I think of as “ye olde manuscript”: yellowed pages, brownish around the edges from years of wear. Everything about the design, from text fonts and sizes, to layout, to animations is interesting without being wearying and suits the dreamy oddness of the tale. Both an abridged version, with all the interactive components, and full text are available. Mushrooms, hookah smoke, a “Drink-Me” bottle, and more float through the pages, where they can be manipulated by moving the iPad. The developers chose not to include narration, perhaps to keep enhancements from becoming a distraction in a story that requires attention. Not a bad choice, considering that Alice is a mature story, best enjoyed by children old enough to read it on their own or shared with younger children by reading aloud with an adult. For ages 5+.

Bartleby’s Book of Buttons, Volume 1: the Faraway Island by Henrik and Denise Van Ryzin (illustrated by Henrik) and developed by Monster Costume, approaches storytelling as a puzzle or game: the reader/player moves through a simple story by solving the puzzles presented on each page. Buttons must be pressed, keys turned, gadgets fiddled with in order to progress to the next page. Mr. Bartleby is a retro-looking guy, who reminds me of the Duplo people my kids played with (back in the day, before they got limbs, hair, and molded facial features). His defining characteristic is his enthusiasm for buttons, switches, and dials. Future English majors may be frustrated by the problem-solving requirements of this story (though it's not that hard and I’m sure it is good for them); analytical and mechanical types will love it. For ages 4-10.

Can we ever tire of Green Eggs and Ham? Certainly not in this version by Oceanhouse Media of the Dr. Seuss classic. The app is developed perfectly for its audience: beginning readers. In “Read to Me” mode, words light up as they are narrated and can be repeated if touched. Poke any object (sky, hat, bush, house, Sam-I-Am, etc.) and the word for it will appear. If the narration for that page is finished, the word will also be pronounced. Small sound effects, like squeaking mice, unobtrusively add humor to the story. In “Read It Myself” mode, background music (only slightly annoying) takes the place of narration, with the same highlighting and pronunciation features. “Auto Play” is similar to “Read to Me,” plus automatic page turns. All in all, it’s a great design that satisfies the needs of children at several levels: an entertaining story for preschoolers; an introduction to words and meanings for those just beginning to decipher words; and a confidence-building experience for children learning to read on their own. For ages 2-8. (Also available for iPhone and iPod Touch.)

Can we ever tire of Green Eggs and Ham? Certainly not in this version by Oceanhouse Media of the Dr. Seuss classic. The app is developed perfectly for its audience: beginning readers. In “Read to Me” mode, words light up as they are narrated and can be repeated if touched. Poke any object (sky, hat, bush, house, Sam-I-Am, etc.) and the word for it will appear. If the narration for that page is finished, the word will also be pronounced. Small sound effects, like squeaking mice, unobtrusively add humor to the story. In “Read It Myself” mode, background music (only slightly annoying) takes the place of narration, with the same highlighting and pronunciation features. “Auto Play” is similar to “Read to Me,” plus automatic page turns. All in all, it’s a great design that satisfies the needs of children at several levels: an entertaining story for preschoolers; an introduction to words and meanings for those just beginning to decipher words; and a confidence-building experience for children learning to read on their own. For ages 2-8. (Also available for iPhone and iPod Touch.)

To me, the most interesting aspect of these five iPad story apps is how each takes a different, but successful, approach to storytelling. While I still hope that paper books will continue to exist – just as I still love to listen to a good, old-fashioned oral story -- I can’t help being excited by the potential for new and creative ways of digital storytelling.

P.S. Thanks, Marianne and Steve, for letting me borrow your iPads!

PopOut! The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter and developed by Loud Crow Interactive, Inc., combines the traditional look of Potter’s work with the feel of a pop-out/lift-the-tab book – except the manipulation is digital. Layers give a 3-D effect, with wriggling, spring-loaded bunnies, free-floating leaves and berries, and digital tabs that slide the characters around to create movement. Classical music and twittering birds help set the scene for the tale, which can be read silently or narrated. Words are highlighted as they are read aloud, making it easier to follow along. It’s great fun to slide Peter under the fence with a moveable tab, with the added plus that this tab will never bend and break. A bookmark tab on every page pulls down a thumbnail storyboard for selecting pages, a handy navigation feature. My only quibble with the app is this: with narration on, the sounds that busy fingers can initiate by touching characters compete with the telling. I would prefer them to pause until the text is read, or chatter more quietly. In all other aspects, it’s a lovely production that honors and extends the original. For ages 2+. (Also available for iPhone.)

Teddy’s Day is based on a 1994 story by Bruno Hächler and illustrator Birte Müller. App developer Auryn, Inc. has transformed a sweet, imaginative story into a sweet, imaginative story chockfull of creative surprises and interactive opportunities. Narration by a young girl sets the child’s-view tone of the tale. I love the pacing of the story and interactions. If you try to move through too quickly, you’ll miss the fun. Instead, after the text is spoken, on-screen highlights briefly shimmer, indicating opportunities for further exploration. These interactions lead you deeper into the story world. Another great feature is the chance to digitally paint pictures, which are then incorporated into the illustration. A spot-on story, interactions that enhance the telling, interesting perspectives, and opportunities to be part of the creative process combine wonderfully to tickle the imagination. For ages 3-7.

Alice – yes, the Alice of Wonderland fame by Lewis Carroll – combines the classic illustrations by Sir John Tenniel with pop-up style in this app from Atomic Antelope. Lush colors are set against a background I think of as “ye olde manuscript”: yellowed pages, brownish around the edges from years of wear. Everything about the design, from text fonts and sizes, to layout, to animations is interesting without being wearying and suits the dreamy oddness of the tale. Both an abridged version, with all the interactive components, and full text are available. Mushrooms, hookah smoke, a “Drink-Me” bottle, and more float through the pages, where they can be manipulated by moving the iPad. The developers chose not to include narration, perhaps to keep enhancements from becoming a distraction in a story that requires attention. Not a bad choice, considering that Alice is a mature story, best enjoyed by children old enough to read it on their own or shared with younger children by reading aloud with an adult. For ages 5+.